“You’re such a talented musician, Suz!” This is a sentiment I have heard countless times from hundreds of well-meaning people. I heard it as a 5-year-old kid after piano recitals. I heard it after being picked as first chair of the middle school orchestra. I heard it when I won piano competitions in high school. I heard it in college from the professor of the one music course I took. And of course I hear it now from people after shows.

But for the majority of my life that phrase was painful to hear. The instant someone said it I would scoff inside myself, knowing they knew nothing about who I was and were just saying that because I accurately played the notes I read off a page. And if they were notes for voice or violin, I executed them in tune. I thought of music as execution. I knew I was dexterous. My fingers were nimble. I had control over their movements. Yes, I had a good ear. Sure, I was good at memorizing. And best of all, I didn’t have much stage fright. Playing music wasn’t hard for me. It was more like a chore, but a chore I didn’t mind doing since it seemed to elicit the praise I craved.

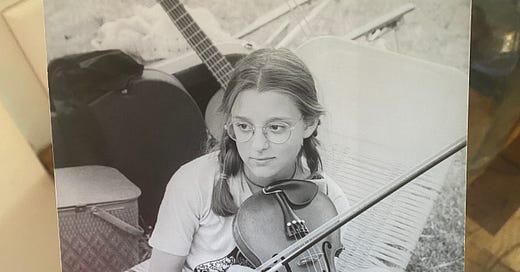

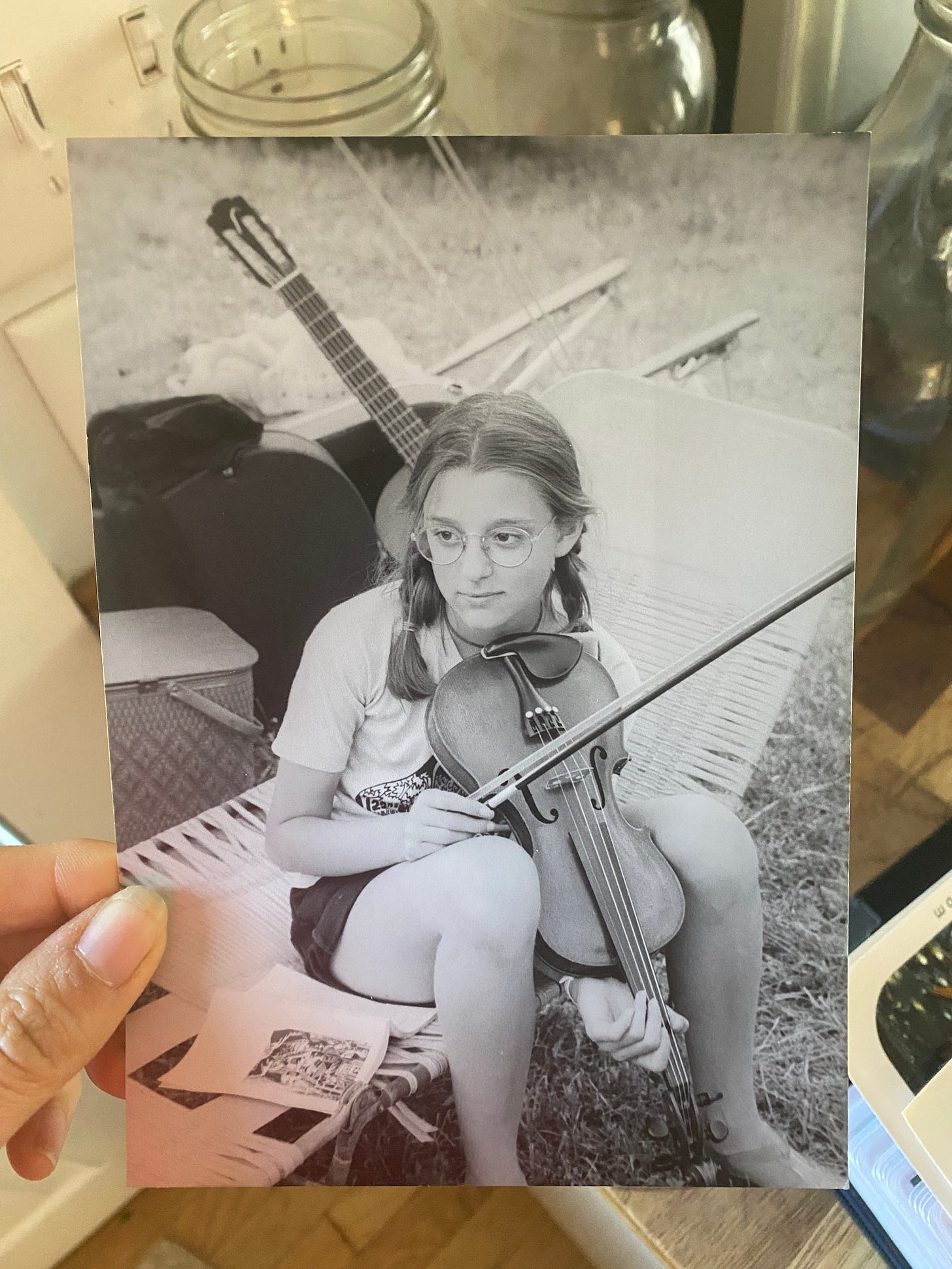

Through the daily practicing I was expected to do as a kid, I learned to transmit small black dots and lines from a page through my optic nerve into my brain and out the muscles of my fingers or vocal chords. I memorized dozens of fiddle tunes. Through hours of singing rounds on the drive into town I had learned to hold my note even when others were changing theirs. I sang in choirs to please my parents, not even knowing how to dare to say no, and learned to maintain my melody while simultaneously listening to the others to make sure I was in tune and in time. I could even mimic my piano teacher playing “emotionally” by crescendoing and decrescendoing at appropriate times based on when she changed volume or tempo.

Music was a cut and paste task. It was rote. And though it might sound beautiful sometimes, and I might have not missed any notes, or gone off key, I knew it was not art. It was a skill I had mastered. And once I really “got good at it” performing music became a way I could gain approval from others and win the competitions and wow people. I liked wowing people. I liked that affirmation. But I never wowed myself with any feelings of connection the way I do now.

But never did I have any sense of my own emotion being involved in the music. The emotions I remember most were resentment of all the practicing. Embarrassment when I hadn’t practiced and knew the teacher knew. Pride at getting the awards, the prizes and the honors though often thinking I lived in a small town without much competition so I was just the best of the small batch. And I often had an overwhelming feeling of shame at knowing that those people who told me I was talented must not know what real art was. Or what true musicianship was. It wasn’t quite imposter syndrome, though it had that flavor; it was a deep sense of knowing that the praise I received for my “emotional” playing “full of feeling and dynamics” that I got points for at the contests was not based on any emotion from inside me. Music didn’t have meaning. It felt more like performing three-dimensional math problems over and over for a crowd who clapped. Music didn’t mean anything to me the way I now know, when done authentically, it can be a life-changing gift for both the giver and the receiver.

My first taste of using music to express or augment my own emotional terrain was as a kid riding my pink sea princess bike down the gravel driveway. Sitting on the faux leather of the banana seat I would sing Yesterday at full volume into the wind. And for those moments I would truly feel my arms ripple with chills and my stomach curdle to hold the sadness offered by the minor chords of that song. On occasion, (only when I was alone in the house as a teen) I tried to play my own chords to feel the hollowness in a deeper way than I could have without the soundtrack I was creating.

But with two brothers and a house full of company, I rarely had time alone, and was painfully embarrassed to play any improvisational music within earshot of any other human, So like the good girl I was, I stuck to the safety of executing the heartbreaking works of Debussy and Ravel and other old dead French men.

Only once I turned 40 and had decades of performance behind me did I ever have the true experience of expressing myself in music. I suppose what changed was multi-layered. The pandemic gave me time to stop touring and actually take a stab at writing my own album, which I did. And the songs touched some of the most emotional touchstones of my life: the suicide of a dear friend in high school, the experience of being cut open after 40 hours of laboring to give birth to my first child, the burden of depression, and the complexity of mania.

The 15 years of playing in the band truly allowed me to master an instrument. Not that one is ever a master over her instrument. But maybe I should say it took 35 years and hundreds of shows to be able to be in a deeply satisfying conversation with my violin.

And now my goal, my only goal really, is to reach for those moments of transcendence when I let my instrument do the talking and I'm just there as a shepherd. Moments when I watch my fingers and ears and spirit working effortlessly, in tandem, to make a story out of notes and crescendos. And for those of us lucky enough to play with lovers and friends, there are enough conversations to last a lifetime. Maybe more.

Thank you for allowing yourself to grow. We are honored that you share your music with the world. ❤️

Beautifully and expressively written. I'm so glad you haven't given up. xo